Today a federal district court judge ruled that “Happy Birthday to You” is not under copyright and belongs in the public domain. The ostensible copyright holder, a subsidiary of Warner Music, has been collecting over $2 million a year from filmmakers, artists, and others using the song. The story has been portrayed as a David vs. Goliath struggle between a major record label and four small artists, but while the case makes a nice, little human interest story for pop culture-watch journalists, it highlights a broader problem with our copyright system.

Copyright protection in the United States was written into the US Constitution which sought to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” It’s worth noting that the purpose of the copyright system was to encourage innovation; rewarding the creator was a means to an end, not the end itself.

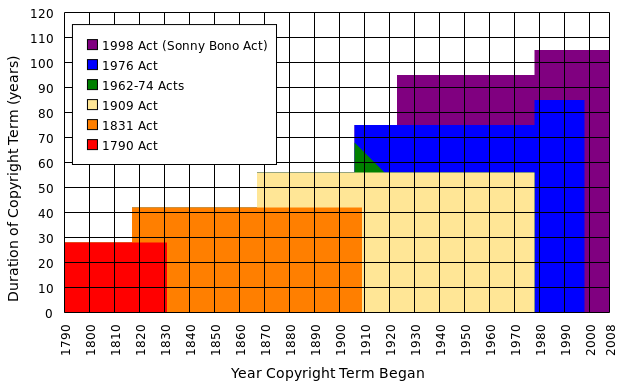

At first, copyright protection lasted for 14 years from the date it was granted with the option of an additional 14 year renewal so long as the creator was still alive and kicking. That comes out to a state-protected monopoly on that text or artwork lasting a maximum of 28 years. Congress believed that bolstering the potential for profit would encourage creators to experiment, while limiting the total length of copyright protection would prevent creators from resting on their laurels and allow others eventually to use their ideas once they’d reverted to the public domain.

But as the handy chart above demonstrates, since 1790 the length of copyright protection has ballooned, with the most recent change extending it to the full life of a creator plus fifty years. The motive isn’t surprising. There’s a great deal of money to be made by those who inherit copyrights. A bestselling book or song could make not only its creator very rich, but, assuming they live to a relatively ripe old age, the next two generations of their family. Corporations have been particularly strong proponents of extended copyright terms, especially the Walt Disney Corporation, which deploys fleets of lobbyists every time the copyright to Mickey Mouse comes close to expiration.

Copyright has turned into a kind of corporate welfare. While the standard for individual creators is life + seventy years, for works of “corporate authorship” it’s a flat 120 years. Given the high cost of enforcing copyright claims against infringement–the armies of lawyers and trial costs–the system disproportionately enriches large corporations while providing little benefit to smaller authors.

The major downside of a vastly extended copyright term is that it skews the balance between profit and innovation all out of whack. This isn’t to say that copyright should be done away with entirely, but it does suggest that copyright protections are so strong that they have begun to hinder rather than advance innovation. We are too far to the right on Alex Tabarrok’s curve (and copyright protections are longer/stronger than patent protections).

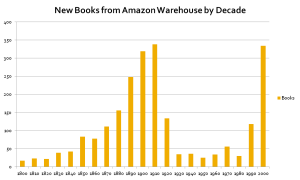

Take, for example, the perverse, unintended consequences of extended copyright provisions on book publishing. Books published prior to 1923 are all in the public domain today, but those from after 1923 were under extended copyrights. Even those books for which copyright may have lapsed still remain under a cloud of potential legal claims. This is why Google Books–that great boon to historians–is chock full of works from pre-1923, but few works from after that date are fully accessible.

As others have pointed out, the twentieth century is a “lost century” for American publishing. Few books from the mid-twentieth century are in print and widely available. While the elite of successful authors have become rich as a result, the works of smaller authors languish in obscurity. For the better part of a century, egregious copyright extensions have shrunk the American canon by discouraging niche literary interests.

Think about it this way. The current system boosts sales and republications for a small number of bestselling books by discouraging the same for a much larger number of books published in smaller batches. It’s a transfer of profits and readers from the many to the few. I suspect that readers in the 19th century read a much more varied selection of books, but by the mid-20th century a larger mass audience consumed the same basic literary diet.

The historian in me can’t help wondering how that played into the creation of the post-WW2 era of consensus. Media historians have explored the role played by network control of the airwaves, but I’m not sure I’ve seen similar work done on how the shrinking horizons of book publication worked in a similar fashion by encouraging mass consumption of literature. How might that have affected mid-20th century American culture?

And on the flip side, if the implosion of network control led to the explosion of innovation that we associate with cable television today–with channels and shows dedicated to every possible taste, ideology, religion, and ethnicity–could the same be true if the copyright system were pruned back? I can’t help but suppose that without the copyright-induced barrier to niche publication, genre fiction might have looked less (ostensibly) white and male. If so, that would make the current imbroglio in the world of science fiction a legacy of unintended legal consequences rather than a referendum on who gets to identify as a “nerd.”