The Ted Strikes Back

In my last post I dug into the South Carolina Republican primary results to suss out the implications of evangelical support for Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio. Since then, Rubio has dropped out, leaving only Trump and Cruz with a shot at reaching the delegate threshold needed to avoid a contested convention. Trump remains the frontrunner, but Cruz’s campaign received a significant boost by winning an outright majority of the vote in Utah, giving him all the state’s delegates.

Why did Cruz win? Certainly, a flurry of campaign pitter-patter in the days leading up to the caucuses hurt Trump’s chances–including Mitt Romney’s endorsement of Cruz and the unseemly back and forth over the relative physical attractiveness of the candidate’s wives–but given that Cruz pulled 69.2% of the vote versus Trump’s 14%, the outcome wasn’t dictated by late-deciding swing voters.

No, Cruz won because he was the overwhelming favorite of the largest voting bloc in Utah: Mormons. As you can see, there was a strong, positive correlation between Mormon adherence rates by county and the percentage of voters who pulled the lever for Ted Cruz. The side-by-side map comparison isn’t as distinct as the one I made for South Carolina (in part, I suspect, because of the visual distortion caused by the large, sparsely populated rural counties), but the line of best fit is actually even more compelling.

I’d like to note that the relationship would be even stronger if we took into account the population density of the counties. Let’s compare two counties with similar adherence rates, Daggett and Salt Lake. Since I gave all counties equal weight, Daggett County (total population: 1,059) and its 94 caucus goers counted just as heavily as Salt Lake County (total population: 1,029,655) and its 46,723 voters. Indeed, the outlying data points tend to be thinly-populated counties like Daggett.

That’s not surprising. Bear in mind that these are caucuses, which tend to feature more variability than primaries. Also, smaller sample sizes lead to noisier data. When you’re dealing with a sample size of just 94 caucus goers in a single precinct, one particularly persuasive speaker can easily swing a dozen votes and help their candidate outperform the state average in that one county. If we accounted for population density, the line of best fit would be even steeper.

It doesn’t take more than a glance at the Utah data to see that Ted Cruz did best in places with the most practicing Mormons. Indeed, Cruz earned a significantly higher share of Mormon voters than he did evangelical voters in any other state. At first blush that might seem surprising. After all, Cruz is a member of a Southern Baptist church and his father is a Pentecostal pastor. Indeed, when I hear Cruz give his stump speech I’m reminded of all the fundamentalist summer camps I attended as a kid; he’s got the southern evangelist’s cadence and pitch down pat. He walks like an evangelical, quacks like an evangelical…yet he swims like a Mormon. What gives?

The Return of the Mormon Moment

Religious scholars who study Mormonism were suddenly in demand in the spring of 2012. Former Massachusetts Governor and dedicated Mormon Mitt Romney was the frontrunner in the Republican race. And journalists love it when odd religious groups burst onto the national political scene. Less than forty years earlier Newsweek had declared that 1976 was the “Year of the Evangelical,” as Southern Baptist Sunday School teacher (and sometime Georgia Governor) Jimmy Carter rode a wave of evangelical support into the White House. And in 2012 Newsweek jumped on a new trend, with Mitt Romney heralding a “Mormon Moment” as conservative Catholics, evangelicals, and Mormons formed a new faith-based coalition.

Although I couldn’t track it down, I remember a 2012 interview with a South Carolina Republican Party doyen who was also a Southern Baptist. The reporter asked her, “Mitt Romney is a Mormon. Do his theological differences bother you given that you’re an evangelical?” She stoutly replied, “Well, he says he loves Jesus and that’s good enough for me!” In the end, Newt Gingrich, a twice-divorced Catholic, actually won South Carolina and outperformed his average among evangelicals. But Romney won a larger percentage of the evangelical vote than Ron Paul, the only evangelical candidate in the race at that point. And in the general election that year, white evangelicals preferred Mormon Mitt Romney over Protestant Barack Obama by 69% to 30%, a higher ratio than either John McCain or George W. Bush received from them in 2000-2008.

Mormons are returning the favor in 2016. That’s not to say that all Mormons are lockstep with Cruz on all issues. For example, the Church is less nativist on immigration than Ted Cruz’s other supporters. The Mormon Church President supported 2014’s failed bi-partisan immigration bill, the same measure which Ted Cruz now brags about defeating. In part, that’s because there are more than twice as many Latter Day Saints living abroad as there are in the United States; they are more truly a global church than any individual American Protestant denomination (with the exception of the Assemblies of God, which not coincidentally also supports comprehensive immigration reform). American Mormon’s internationalism is further boosted by the two years of missionary service that most undertake, often overseas.

Attack of the (Second Great Awakening) Clones

There’s a nice parallel between evangelical support for a Mormon in 2012 and Mormon support for an evangelical in 2016. While this strategic alliance may appear to be a recent phenomenon, it draws on a shared history and theology that goes back to the 19th century. What’s surprising about the rapprochement between Mormons and evangelicals isn’t that it has occurred, but that it’s taken this long.

Cruz’s evangelicalism and Romney’s Mormonism are both children of the Second Great Awakening(s). Now, I’m not suggesting that we collapse the theological tensions between Mormons and evangelicals. Mormon views on Christology, revelation, and soteriology are so divergent from Christian beliefs that I am comfortable defining them as unique religions, not just different denominations within a shared faith. But while they differ on matters of doctrine, they share an elevated view of America’s role in the history of redemption. That affects how both groups engage in politics. In other words, their systematic theology might differ, but their political theology is really quite similar at key points.

In part that’s because the Book of Mormon made explicit what early 19th century evangelicals believed was implicit in the Bible. For example, both Mormons and 19th century evangelicals encoded racism in their respective sacred scriptures. By the 1820s pro-slavery evangelical theologians had inserted race into Bible stories, like that of Ham or Cain, which made no mention of skin color. And when Joseph Smith wielded his seer stone, he found that Moroni had quite a good grasp on the racial views of antebellum Americans considering that he was a resurrected, angelic being from the 5th century AD. Mormons didn’t have to read race into the stories of Cain or Ham; the Book of Mormon baldly stated it.

In part that’s because the Book of Mormon made explicit what early 19th century evangelicals believed was implicit in the Bible. For example, both Mormons and 19th century evangelicals encoded racism in their respective sacred scriptures. By the 1820s pro-slavery evangelical theologians had inserted race into Bible stories, like that of Ham or Cain, which made no mention of skin color. And when Joseph Smith wielded his seer stone, he found that Moroni had quite a good grasp on the racial views of antebellum Americans considering that he was a resurrected, angelic being from the 5th century AD. Mormons didn’t have to read race into the stories of Cain or Ham; the Book of Mormon baldly stated it.

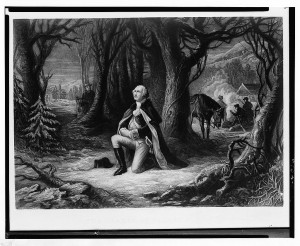

Today, evangelicals and Mormons both tend to sweep these old views on race under the carpet, but their views on America’s exceptional role in God’s plan for humankind also reflect 19th century cultural values. Second Great Awakening evangelicals believed that God would bless the nations of the world through the Christian example of America. After all, hadn’t John Winthrop declared in 1630 that the Massachusetts Bay Colony would be a “city upon a hill,” a reference to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount? And hadn’t the Founding Fathers enshrined Christian values in the US Constitution and through early legislation?

Evangelicals were warming up to the notion that America was, at least temporarily, fulfilling Israel’s former role as God’s chosen nation. While this impulse would come to full flower in the 20th century with Christian Zionism, 19th century preachers like Charles Finney and Lyman Beecher had argued much earlier that America would usher in the postmillennial reign of Christ on earth. A little bit of revival here, some social reform there, a dab of the American missionary movement everywhere, and the world would be ready for Christ’s return. In Beecher’s words, America was “destined to lead the way in the moral and political emancipation of the world.”

And the actual religious history of America could always be rewritten to order. As the Founding Fathers died off, veneration of the revolutionary generation reached a fevered pitch. The major political parties of the time battled over who best upheld the values of the Founders. Evangelicals and other religious groups followed suit. I’ve written before about “Parson” Mason Locke Weems, but there was a cottage industry of authors who embellished the lives of the Founders to make them more pious and more orthodox. It was a retroactive “evangelicalization,” a literary baptism for the dead.

And the actual religious history of America could always be rewritten to order. As the Founding Fathers died off, veneration of the revolutionary generation reached a fevered pitch. The major political parties of the time battled over who best upheld the values of the Founders. Evangelicals and other religious groups followed suit. I’ve written before about “Parson” Mason Locke Weems, but there was a cottage industry of authors who embellished the lives of the Founders to make them more pious and more orthodox. It was a retroactive “evangelicalization,” a literary baptism for the dead.

But whereas evangelicals only inferred a sacred role for America from the Bible, the Book of Mormon explicitly codified American exceptionalism. Moroni took matters a step farther, revealing to Joseph Smith that America was not just a rough corollary for Israel. No, America was populated by actual Israelites. As the story goes, several of the ten lost tribes of Israel, which had been taken captive by the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC, escaped to the Americas. These Nephites colonists built an ancient civilization complete with cities, kings, and currency; but they were opposed by the wicked Lamanites, also immigrants but whose rejection of God was marked by their dark skin (again, with the race obsession). The groups warred for a while, but eventually the Nephites also rejected God and intermarried with the Lamanites, producing a degraded remnant that the early Mormons identified as the ancestors of the Native Americans. Furthermore, Joseph Smith believed that 19th century Mormons were themselves blood descendants of the lost tribe of Ephraim.

Modern archeologists have found no trace of this pre-modern, Israelite civilization in the Americas, but at the time it was transcribed the Book of Mormon narrative adhered closely to widespread Christian speculation about a connection between Native Americans and the ten lost tribes of Israel. As ahistorical and fantastical as it sounds today, the Mormon account of the ten lost tribes seemed quite believable to the many evangelicals who converted to Mormonism. America was quite literally a replacement for ethnic Israel, a new land populated by the remnants of several tribes. And Mormons had divine warrant to go out and gather the other lost tribes so they could return to their new homeland in New York Illinois Utah.

Later Mormon Presidents–who can speak ex cathedra—specified that the US Constitution was inspired. President Ezra Taft Benson called America God’s “base of operations” from which He would prepare a “new gospel dispensation” for the salvation of the nations. It’s no accident that Benson played a major role in bringing Mormons into the New Right during the mid-20th century. (Imagine the political ramifications if a Catholic Pope had joined the John Birch Society. That’s Benson for you.)

Space Jesus: The Mormons Awaken

Given the significant overlap between 19th century Mormon and evangelical views on America’s divine calling, it’s not surprising that their 21st century descendants are getting along so readily, especially now that some of the rough edges (*cough,* polygamy, *cough*) have been worn off, thus reducing the cultural and religious tension between Mormonism and broader American Christianity. There’s a potent symbol of that rapprochement in the main Salt Lake City Temple. If you take a tour, you’ll end by staring up into the face of Space Jesus.

That’s one of the few concrete moments I remember from my visit to Salt Lake City as a 12 year old kid, which also happened to be about when I first watched a movie series set “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away….” It’s a fitting image. After all, Mormons are rightfully known for their love and authorship of amazing fantasy and science fiction. And some other…stuff. Hey, no religious tradition gets EVERYTHING right.

It’s not hard to see why Ted Cruz’s Christian Nationalist rhetoric appeals to conservative Mormon voters. As he told Breitbart News, America is “a unique nation, the indispensable nation, a clarion voice for freedom that we will speak for liberty, for truth. That we will be as Reagan put it, a shining city on a hill.” (The estate of Jesus Christ has since notified the FTC that it trademarked the phrase “city on a hill” some 2,000 years ago. The pending lawsuit may be settled out of court, depending on when the next Judgement Seat session is convened.)

But these word choices–America as “unique” and “indispensable”–are coded for Mormon and evangelical ears alike. Potential Cruz supporters who aren’t religious won’t necessarily pick up on the Christian Nationalist overtones. Those who are Christian Nationalists understand that Cruz is signaling that he’s one of them without coming right out and saying so. His current slogan is “Reignite the Promise of America.” Several of his Super PACs are named “Keeping the Promise.” That kind of language appeals on an almost subconscious level to evangelicals and Mormons who believe that God and the Founding Fathers entered into a special, covenantal relationship. If America is to prosper, it needs to keep up its end of the bargain with God, just like Israel before it.

And while Cruz never explicitly says that he believes the Constitution is divinely inspired, he gets as close to the curb as he can without scraping his rims. In his announcement speech at Liberty University, the largest evangelical university in the world, Cruz said, “God’s blessing has been on America from the very beginning and I believe God isn’t done with America yet. It is a time for truth. It is a time for liberty. It is a time to reclaim the Constitution of the United States.” Inspiring words that he followed by asking the audience to “text the word Constitution to the number 33733” and join his campaign.

The message is certainly getting through to Cruz’s biggest Mormon fan, talk radio host Glenn Beck. In a joint appearance with Cruz at a pentecostal church in South Carolina, Beck begged the attendees to “Ask our dear Lord to show you who the man is that has the integrity, who has the connection, who will fall to his knees at the Resolute Desk, who, before he acts doesn’t think of a poll but looks to the Constitution and the holy scriptures; our Bible and the Constitution both come from God, they are both sacred scriptures!” While elevating the US Constitution to the level of divine inspiration is perfectly in keeping with Mormon doctrine and practice, you would expect evangelical listeners to at least shift uncomfortably in their seats when faced with a heterodox statement about extra-Biblical revelation. What Beck got instead was applause.

One of the most surreal moments in an election cycle that even the Dadaists would have found far-fetched was the spectacle of Mormon Glenn Beck and Southern Baptist pastor Robert Jeffress sparring over whether God preferred Ted Cruz or Donald Trump. While speaking to a Mormon audience in Utah, Beck implicitly appealed to the Book of Mormon’s ancient American history of struggle between the people of God and the Lamanites. “The Book of Mormon is a book that was given to us for this time in this land. And it explains exactly what it’s going to look like when trouble comes. And I don’t know about you, but I can put new names against old names, and it all works.” Beck’s hope was that if Mormons stood up and delivered a win for Cruz in Utah, then evangelicals would start “listening to their God” and back Cruz in larger numbers.

Jeffress took umbrage at Beck’s criticism of southern evangelicals, although not Beck’s assertion of American exceptionalism. Just a month or so before, Jeffress had introduced Donald Trump at a rally in Texas, right in Cruz’s backyard. In a tweet–since deleted–Jeffress explained his support for Trump with an appeal to Matthew 5:13, the Sermon on the Mount again: “You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again.” Christians were called to influence the broader culture and Jeffress thought Trump was the man for the hour. Thus Beck’s comments struck Jeffress as “wacko” and he found himself “somewhat puzzled that Beck claims to know how the God Christians worship would vote in the Republican primaries” given that he is a Mormon.

Indeed, if you weren’t familiar with the long history of Mormon/evangelical belief in America’s sacred calling, I suppose it might have seemed “wacko” to witness Mormons battling for the evangelical candidate and Southern Baptists backing a twice-divorced, Easter-and-Christmas, mainline Protestant. All it takes is mentally inserting the adjective “American” in front of the phrase “city on a hill,” ignoring the Sermon on the Mount’s context, and waiting for applause.