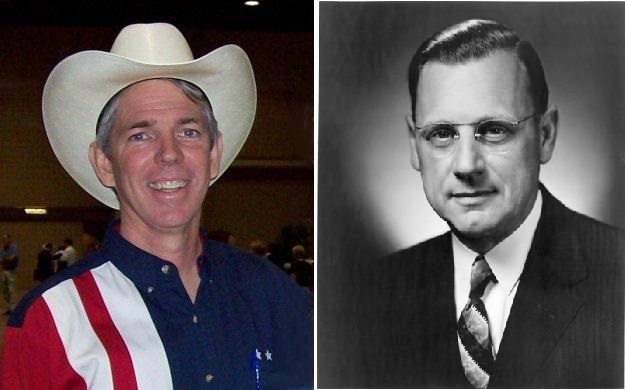

Photo Rights, David Barton: cwmemory.com Photo Rights, Harold Ockenga: Fuller Seminary David Allan Hubbard Library

American Christian nationalists believe that God anointed the United States of America as a spiritual successor to the Old Testament nation of Israel. America was chosen, so the story goes, because of the faith of the colonial settlers. The Puritans founded an American “city on a hill” that was tasked with an exceptional mission to shine the gospel light on the rest of the world. Then the Founding Fathers, most of whom were evangelical believers, enshrined Christian values in the Constitution. Unfortunately, later generations of Americans have fallen away from that state of grace. But should Americans repent and turn from their secular humanist ways, America might once again find itself the recipient of God’s blessing.

Christian nationalism is both theologically and historically hogwash, but it’s not my purpose in this post to specify why; better historians than I have already given it their best shots. What I do want to point out is that Christian nationalist thinking has been much more mainstream among evangelicals than is commonly portrayed in contemporary discussions about New Christian Right activists.

Take the example of Harold J. Ockenga, who is known for his role in the creation of a “new evangelicalism” during the 1940s and 1950s. Theoretically he represents a milder, less militant form of fundamentalism. Yet here is a 1943 address he gave at the founding convention of the moderate National Association of Evangelicals under the heading, “America Will Determine World Destiny” [emphases my own]:

I believe that the United States of America has been assigned a destiny comparable to that of ancient Israel which was favored, preserved, endowed, guided and used of God. Historically, God has prepared this nation with a vast and united country, with a population drawn from innumerable blood streams, with a wealth which is unequaled, with an ideological strength drawn from the traditions of classical and radical philosophy, with a government held accountable to law, as no other government except Israel has ever been, and with an enlightenment in the minds of the average citizen which is the climax of social development.

He continued later,

Apparently the last great privilege of ministering to mankind was committed to this particular nation. That is a tremendous responsibility for which we are answerable. We have the enlightenment. We have the historical tradition. We have the material means. We have the leadership. We have everything which is necessary in order to evangelize the world. Now we have entered into our maturity, and we are facing an accounting for that destiny. If America fails to discharge its responsibility darkness must ensue.

Ockenga was appealing for the creation of a united evangelical front in America. As I argue in my dissertation, this was the moment when “evangelicalism” transformed from a mere description of theology into a term of identity. Ockenga harnessed this Christian nationalist rhetoric because he believed it would unite disparate Protestant groups–including Pentecostals, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists among many other groups–against their common enemies (modernists, Catholics, etc). Christian nationalism has been at the heart of American evangelical identity for much longer than you may have thought.

Ockenga’s speech was transcribed in the Pentecostal Holiness Advocate, vol 27, no 3 (20 May 1943).