I posted recently about a popular myth concerning eighteenth century preacher Samuel Davies. In the story, Davies beards the King of England in his own palace. The story helped nineteenth century evangelicals overlook the pro-British attitudes that the real Davies had espoused, attitudes that were very unpopular after the American Revolution. Myth making always serves a greater political or cultural purpose. We can advance our agenda by burnishing the memory of us and ours (and vilifying them and theirs). So it’s no surprise that nineteenth century evangelical republicans smoothed the rough edges off Samuel Davies.

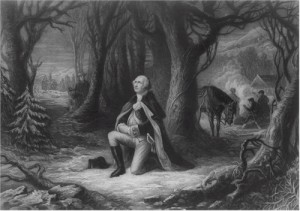

The same can be said for the valorization of the “Founding Fathers.” There’s an entire cottage industry today that exists to uncritically reproduce early nineteenth century myths about the founders. Given the surprising rise of evangelical theology in the decades following the Revolution, these myths tended to write evangelical sentiments back into the memory of the founders. There’s a detailed historiographical debate over exactly what the religious beliefs of men like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were, but suffice it to say they were not evangelicals. (If you’re interested in the topic, I’d recommend starting with either Gregg Frazer or John Fea.)

But it’s worth mentioning that evangelicals aren’t the only ones guilty of spinning myths about the American founding. Given that today’s the Fourth of July, I’ve seen a number of friends post on social media about Sybil Ludington’s ride. In 1777 Sybil–the sixteen year old daughter of a Revolutionary militia colonel–rode forty miles (twice the distance ridden by Paul Revere!) to raise the militia in time to respond to a British thrust into New York. Because of her bravery, that militia unit aided the Revolutionary forces in driving the British back to Long Island. George Washington himself thanked the young girl for her service.

The story, however, is very poorly sourced. It was first written down in 1907, fully a hundred and thirty years after the event, by one of Sybil’s descendants. Both of those facts should raise red flags. There’s a complete lack of primary source documentation for the story; there’s not even any record of the Ludington’s militia being involved in that military action. Of course, it’s all but impossible to prove a negative, but while Sybil’s story might be true in whole or part, it’s best classified as myth rather than history.

The story was first published in 1907 with money provided by the Ludington family. What family wouldn’t want to highlight their ties to the American Revolutionaries? In 1961 the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution commissioned a statue of Sybil. What civic organization wouldn’t want to highlight their town’s ties to the American Revolutionaries? It was a useful myth.

Recently, the story has become even more popular. She is the heroine in children’s books, graphic novels, and she even got her own segment on the PBS show “Liberty’s Kids.” I think the “Liberty’s Kids” episode description suggests why there is a sudden revival of interest in Sybil Ludington:

James learns that all kinds of people can be heroes and that especially includes strong-minded courageous young ladies. Meanwhile Sarah sees Benedict Arnold battle for respect with the same passion he uses to battle the British. She becomes concerned that Arnold’s passions might do what the British cannot – defeat him.

HISTORICAL CONTENT

Sixteen-year-old Sybil Ludington defies the standard view of what is proper for a young lady and makes her own courageous “midnight ride” in Westchester County, New York to help the rebels cause (4/26/77)….

EMOTIONAL TAKEAWAY

Limitations that others place on us cannot stop one from achieving greatness if one’s mind is set on it.

Although reports of the death of evangelicalism in the United States have been greatly exaggerated, we do live in an increasingly post-Christian cultural milieu. Burnishing the credentials of evangelical heroes via myth-making is sooo last century. Instead, we use a new group of myths to advance progressive causes and ideals, like an egalitarian appreciation of the role of women in American history. Throw in a dash of self-esteem psychology, and boom, you have all the ingredients of Sybil Ludington’s ride.