On Election Day last week I lectured on the election of 1968 for my class at Penn State, “From Hippies to Yuppies: America in the Long 1960s.” I am hardly the first to note the many echoes of 1968 on both sides of the contest in 2016. The anger of Bernie Sanders’s supporters at the Democratic Party placing a super-delegate-sized thumb on the scale for Hillary Clinton is an echo, albeit a pale one, of the protests that erupted in Chicago in 1968. To the chagrin of younger, more radical voters, the Democratic National Convention had nominated Hubert Humphrey for President despite the veteran politician winning not a single primary contest. On the Republican side in 2016, Donald Trump’s campaign explicitly embraced the slogans of Richard Nixon’s 1968 and 1972 campaigns, calling for a return to “law and order” and claiming to represent a “silent majority” of American voters (insomuch as 47.3% of the popular vote counts as a majority).

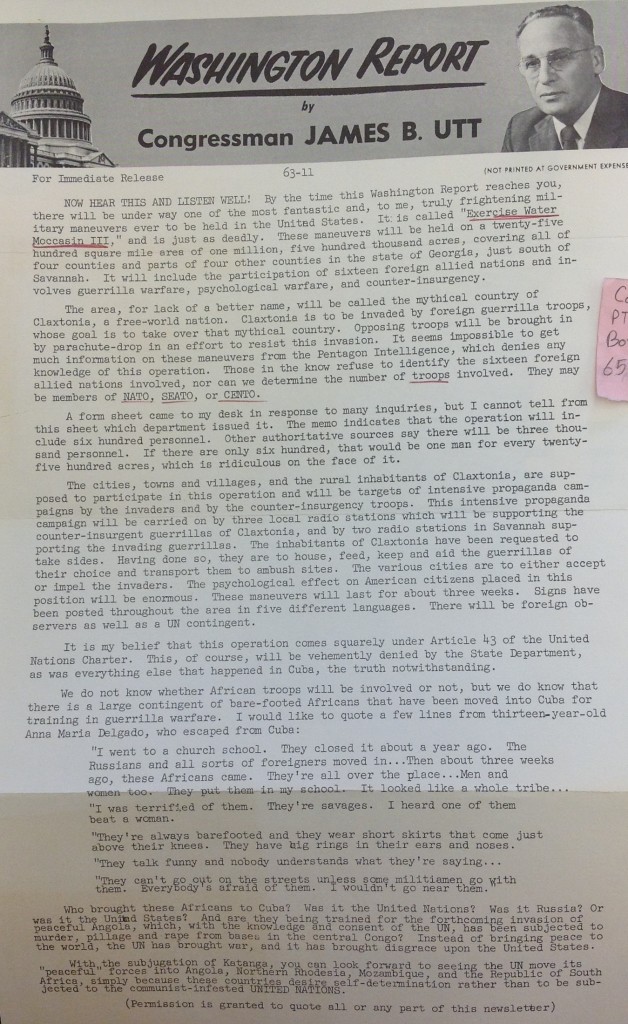

But the strongest resonance between 1968 and 2016 may well be the populist rhetoric of George Wallace and Donald Trump. Both men appealed to white working class voters who felt alienated from the major party establishments. In 1968, white ethnics (Poles, Irish, Italians, etc) had a long tradition of voting for the Democratic Party going back to before the New Deal, but the national party leadership had embraced civil rights reform. Wallace stoked these voters’ anger about a federal government more concerned with giving jobs and welfare subsidies to African-Americans than supporting the white working class. Wallace crisscrossed the South and the Rustbelt promising jobs and a government that prioritized the interests of white workers. Nearly fifty years later, Donald Trump has made a similar appeal but with illegal immigrants as the focus of white resentment rather than African-Americans. (He routinely criticized the Black Lives Matter movement but along another axis that more closely resembles Wallace’s criticism of anti-Vietnam War protesters.)

It can be a mistake for history teachers to spend too much time in class making direct (and sometimes tortured) comparisons between past and present. However, the 1960s fall well within living memory and continue to form the political, cultural, and religious background of our lives today. When speaking of the fall of modern conservatism at the hands of the alt-Right, one must first explain its rise in the late-1950s and early-1960s. When discussing the #blacklivesmatter movement, one must refer back to the civil rights movement in the 1960s, and so on with nearly every facet of contemporary American life.

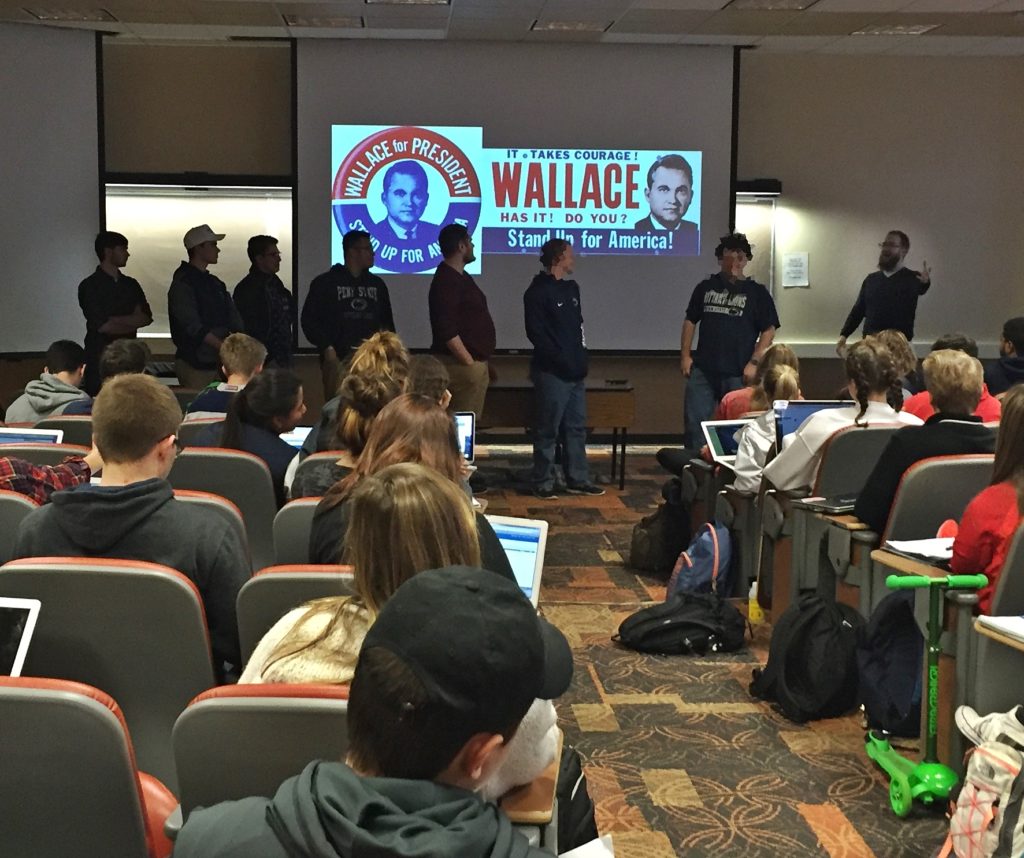

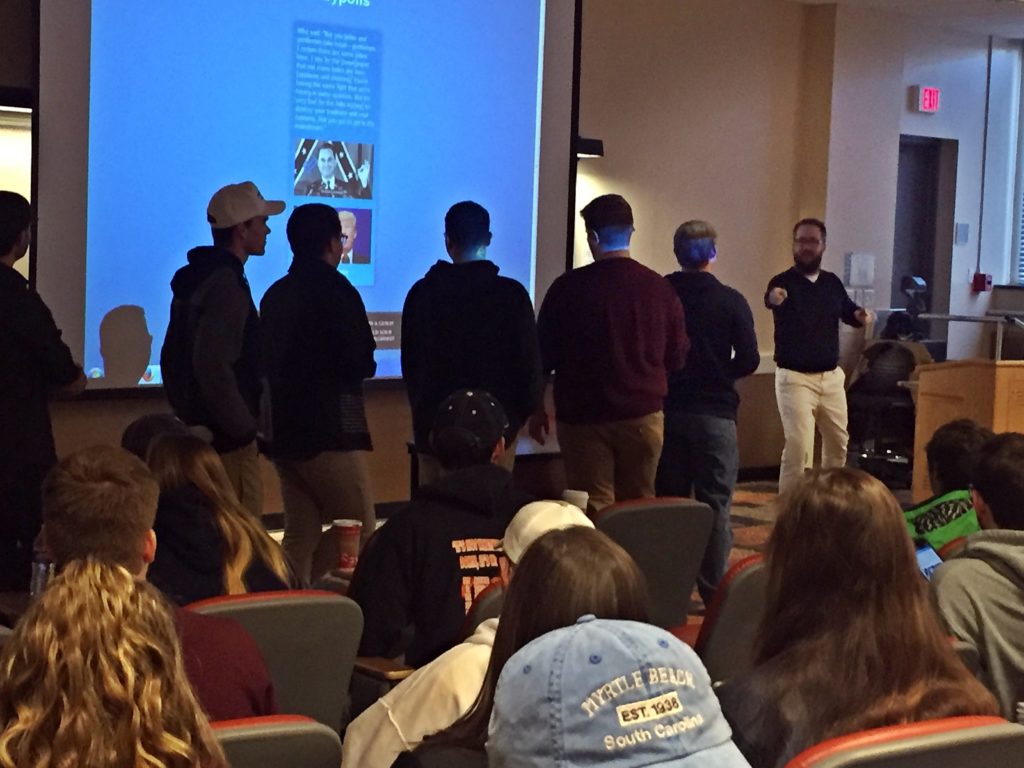

To help my students make some of these connections, I decided to create an in-class game show. Seven students were called to the front of the room. Each was given a microphone and a short quote. If they could correctly guess whether the statement was by Donald Trump or George Wallace, then they would receive a bonus point on their next quiz. If at least four of the seven contestants answered correctly, the entire class would receive a bonus point. To keep the entire class of ~160 involved, I posted an online poll for each quote so that the class could impart the wisdom of the crowd to the contestants. Below I have posted the quotes with links to the online polls. See if you can answer all seven correctly. The answers will be listed at the very bottom of the post, but no peeking.

Question #1: “I remember speaking at Harvard. I made them the best speech they’d ever heard. There are millions like you and I throughout this country. There are more today of us than there are of them.”

Question #2: “But you ladies and gentlemen take heart–gentlemen. I reckon there are some ladies here. I see by the [news]paper that not many ladies are here. [applause and cheering] You’re having the same fight that we’re having in some quarters. But it’s very bad for the folks try[ing] to destroy your traditions and your customs. But you got to get in the mainstream.”

Question #3: “I will be the greatest jobs president God ever created.”

Question #4: “If any demonstrator ever lays down in front of my car, it’ll be the last car he’ll ever lay down in front of.”

Question #5: “I love the old days, you know? You know what I hate? There’s a guy totally disruptive, throwing punches. We’re not allowed to punch back anymore … I love the old days. You know what they used to do to guys like that when they were in a place like this? They’d be carried out on a stretcher, folks.”

Question #6: “I have a great relationship with the blacks.”

Question #7:

Demonstrators: ________ go home! ______ go home!

________: Why don’t you young punks get out of the auditorium?

________: [whispers to someone off camera in audience] What’d you say? You go to hell, you son of a bitch. …

Crowd: We want _______! We want _______!

________ supporter: You ought to take them people over there and put them in a bunch of cages and ship them off in a ship and dump them!

The contestants in my class did very well, answering six of the seven correctly. The average margin for the wisdom of the crowd was 2-1 for the correct candidate. Ironically, one of the contestants was wearing a “Make America Great Again” hat. He received question #6 and answered correctly; you can’t say that he went to polls unaware of exactly what kind of person he was voting for! In any case, I figure that this poll will remain an enlightening classroom exercise for at least the next four years. (#silverlining)

From my fellow history instructors, I would be interested in hearing how you connect past with present in your class and about any exercises you use to do so. Feel free to send me an email or leave a comment.

Question #1: Wallace

Question #2: Wallace

Question #3: Trump

Question #4: Wallace

Question #5: Trump

Question #6: Trump

Question #7: Wallace