I presented a paper at the American Historical Association’s annual conference last January. My paper, titled “Polish Ham, Talk Radio, and the Rise of the New Right,” illustrated the power of conservative radio with the story of a little known yet wildly successful 1962 boycott of Eastern European imports by conservative housewives. Afterwards, David Farber, a professor of history at the University of Kansas, asked me a particularly important question. Before I get to the question, I should note that it was an honor to have him in attendance; my dissertation, of which this paper was a part, can be traced back to a graduate seminar I took with him while he was at Temple University. His encouragement and advice came at a key moment in my academic career.

I presented a paper at the American Historical Association’s annual conference last January. My paper, titled “Polish Ham, Talk Radio, and the Rise of the New Right,” illustrated the power of conservative radio with the story of a little known yet wildly successful 1962 boycott of Eastern European imports by conservative housewives. Afterwards, David Farber, a professor of history at the University of Kansas, asked me a particularly important question. Before I get to the question, I should note that it was an honor to have him in attendance; my dissertation, of which this paper was a part, can be traced back to a graduate seminar I took with him while he was at Temple University. His encouragement and advice came at a key moment in my academic career.

My memory is not exact, but what Farber asked was, “What is the epistemology of Right-wing radio? How did conservative listeners know what they were being told was true?” It was an excellent question. After all, it’s not just that conservative radio listeners believed what they were being told, but that they believed so strongly that it inspired action. Hundreds of thousands of ordinary folks translated radio into activism, the kind of sign-waving, door-knocking, literature-passing, coffee klatch-holding, card party-organizing activism that only true believers participate in. You have to be really sure of something to engage so fully, to commit so much of your resources and time. A vibrant grassroots movement like the New Right of the early 1960s must have required a powerfully convincing epistemology to attract and maintain activists. I stumbled through an answer at the time, but I think I can answer more fully now that I’ve had time to reflect.

The very nature of radio broadcasting as a thing consumed in the privacy of the home or car encouraged listeners to feel a sense of personal connection to the broadcaster. Hearing a voice express emotion is a more intimate experience than reading words printed on a page. Politicians have long taken advantage of this broadcast media effect, like President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famous “Fireside Chats” during the Great Depression. Americans at the time often reported feeling like Roosevelt was talking to them personally, that he truly cared about their individual struggles. Conservative broadcasters in the 1960s benefited from the same effect. Their listeners–who skewed middle-aged, middle-class, and female by a two to one margin–wrote to McIntire and poured out their concerns for their wayward children, ill spouses, and the decline of their nation. A grandmother in Illinois wrote of her concern for her grandchildren who attended a public school since their father had lost his faith in high school (though combat during WW2 partially restored it). A mother in Pennsylvania included a post-script to her letter in order to brag of her tenth-grader’s prize-winning oratory describing the Navajo Indians. A mother in Wisconsin worried about her daughter drinking alcohol, dating a Catholic boy, and refusing to help with household chores; her husband only attended church part-time and didn’t share her concerns. Another woman watched the 1960 election returns until 4am, confessing that she cried herself to sleep after realizing that the Catholic candidate John F. Kennedy had won.

That sense of intimacy fueled a willingness to trust conservative broadcasters when they spoke on political and social issues. A correspondent from Kansas felt that McIntire’s program armed her with the “facts at hand” and made her feel “a place along with many others who are listening.” That last statement is vitally significant. Radio bound listeners not only to the broadcaster but to each other. The Kansan went on to say that she felt “no longer alone and helpless.” And when the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations shut down conservative broadcasting in the late-1960s, these listeners did not just lose a show. No, they suddenly felt disconnected from a movement of like-minded conservatives. As one listener from the southeast corner of Washington State wrote after the local radio station dropped McIntire’s show, “I feel as tho [sic] my life-line has been cut.” This was not merely hyperbole. Every single weekday for the past five, ten, or fifteen years these listeners had turned on their radios and heard Carl McIntire, Billy James Hargis, and other conservative broadcasters tell them that they were part of a national movement to reclaim America for God and the Constitution.

The sharper among my readers have likely already noticed a disconnect between my argument and my chronology. After all, mass radio broadcasting had existed since the 1920s and there had been conservative voices on the air from the beginning. So it’s only logical to wonder why conservative radio broadcasting would have sparked the creation of the New Right in the late-1950s and early 1960s rather than at any other moment in the preceding four decades. Why at that moment did millions of Americans turn on their radios and suddenly find conservative ideas so much more convincing than before?

What changed between the 1920s and 1960s was the sheer number of conservative programs as well as the number and reach of stations willing to air those programs. There had always been conservative broadcasters, like Father Charles Coughlin, but they were confined to a handful of isolated time slots on stations mostly controlled by the major radio networks. You might hear Coughlin criticize the New Deal on air, but he would be followed by a pro-New Deal program or even one of the President’s own fireside chats. Conservative broadcasters in the early 20th century did not, in other words, have their own media ecosystem. Their listeners were exposed to the broader political spectrum. Also, their reliance on the major networks left them vulnerable to cancellation should they be too strident in their political attacks or if they strayed too far from consensus liberalism.

What changed between the 1920s and 1960s was the sheer number of conservative programs as well as the number and reach of stations willing to air those programs. There had always been conservative broadcasters, like Father Charles Coughlin, but they were confined to a handful of isolated time slots on stations mostly controlled by the major radio networks. You might hear Coughlin criticize the New Deal on air, but he would be followed by a pro-New Deal program or even one of the President’s own fireside chats. Conservative broadcasters in the early 20th century did not, in other words, have their own media ecosystem. Their listeners were exposed to the broader political spectrum. Also, their reliance on the major networks left them vulnerable to cancellation should they be too strident in their political attacks or if they strayed too far from consensus liberalism.

But that all changed in the 1950s as the major networks shifted their attention to television. The number of radio station licenses continued to climb steadily, but an increasing number went to small, independent station owners unaffiliated with the big networks. These stations were continually strapped for cash and willing to accept programming from previously unthinkable radicals including conservatives. As a result, conservative broadcasters started popping up all over the country. They cobbled together an informal network of stations that aired predominately conservative programming even if the owners were not themselves conservatives.

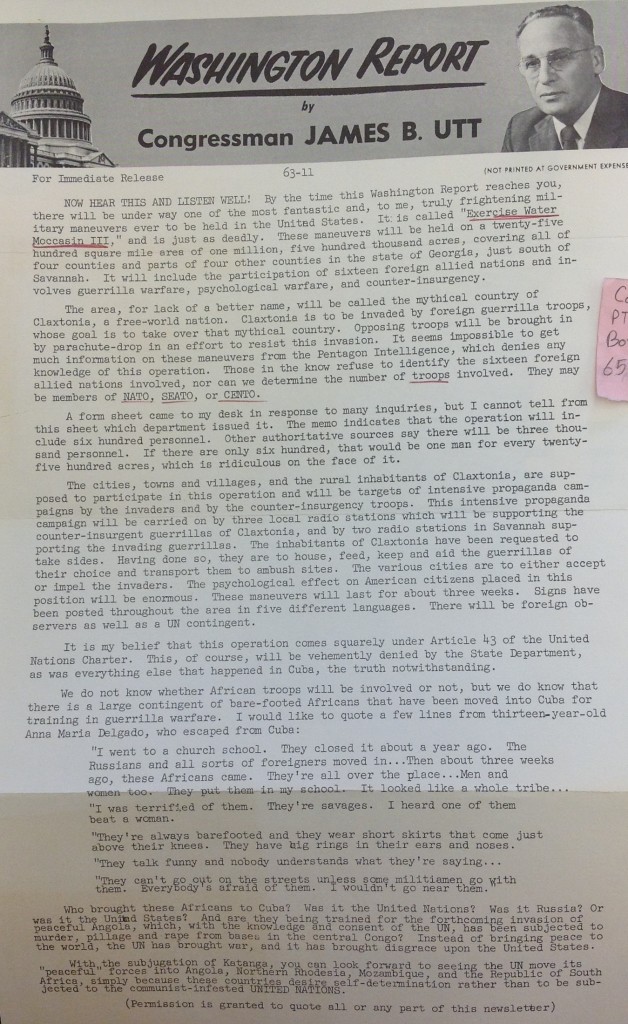

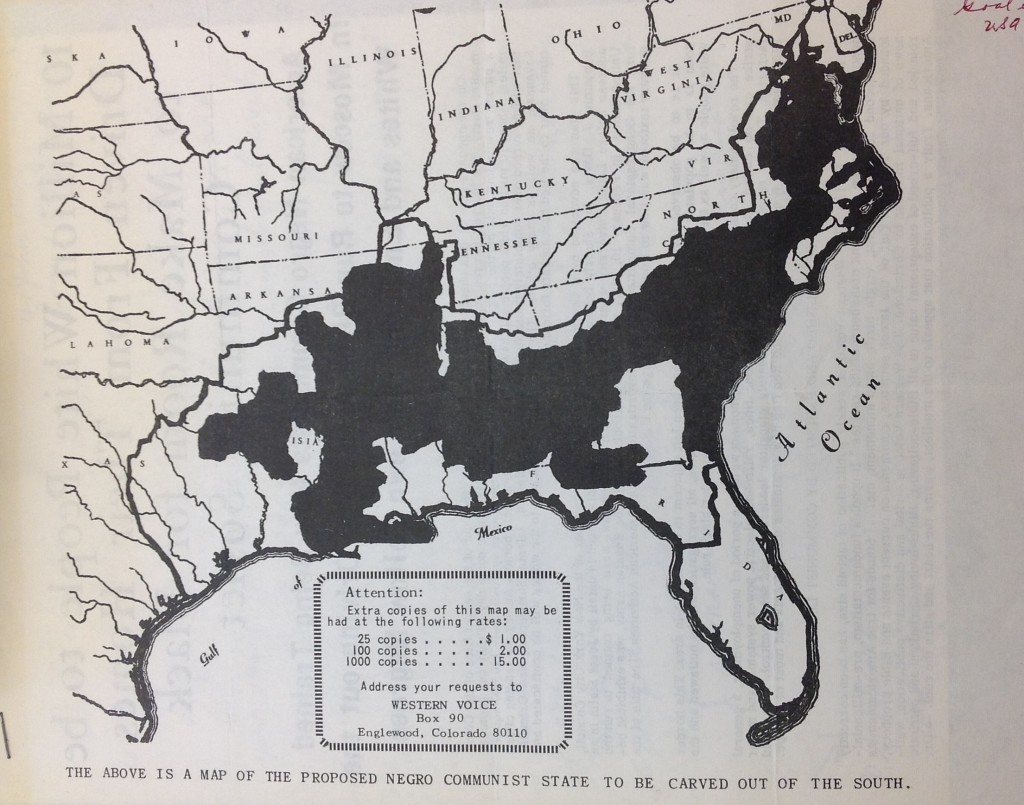

For the first time in broadcast history, the vast majority of Americans could listen to conservative radio programs from dawn till dusk every day of the week. During the morning drive, you might listen to an hour of Dan Smoot attacking the Kennedy Administration’s Cuba policy on Life Line. Then you could listen to Christian Crusade as Billy James Hargis ferreted out Communist-sympathizers at the highest levels of the federal government. Next came Howard Kershner’s fifteen minute weekly sermonizing on “the Christian religion and education in the field of economics.” Perhaps your station, particularly if you lived in the South, aired The Citizens’ Council, the radio home for white massive resistance. During lunch, you might listen to McIntire’s Twentieth Century Reformation Hour as he applauded the Polish Ham Boycott. And so on throughout the rest of the day, one conservative program after another keeping up the same basic drumbeat: Communists were everywhere, the Kennedy Administration was weak, and only conservative action could save America. It was a torrent of conservative ideas and calls to action, the first wave of talk radio.

For the first time in broadcast history, the vast majority of Americans could listen to conservative radio programs from dawn till dusk every day of the week. During the morning drive, you might listen to an hour of Dan Smoot attacking the Kennedy Administration’s Cuba policy on Life Line. Then you could listen to Christian Crusade as Billy James Hargis ferreted out Communist-sympathizers at the highest levels of the federal government. Next came Howard Kershner’s fifteen minute weekly sermonizing on “the Christian religion and education in the field of economics.” Perhaps your station, particularly if you lived in the South, aired The Citizens’ Council, the radio home for white massive resistance. During lunch, you might listen to McIntire’s Twentieth Century Reformation Hour as he applauded the Polish Ham Boycott. And so on throughout the rest of the day, one conservative program after another keeping up the same basic drumbeat: Communists were everywhere, the Kennedy Administration was weak, and only conservative action could save America. It was a torrent of conservative ideas and calls to action, the first wave of talk radio.

When I call this a media ecosystem I’m referring to the manner in which these programs, despite a lack of any coordination, authenticated each other in the minds of their listeners. How did a listener know that what they were hearing was true? Well, an idea would be repeated in slight variations across dozens of programs. Perhaps one broadcaster might be wrong, but an entire channel’s worth of programs? Surely not. These weren’t the ideas of any lone radical; the same basic opinion on any given current event might be uttered by a range of seeming experts, from preachers (McIntire, Hargis, Fulton Lewis), an economist (Milton Friedman), a lawyer (Clarence Manion), a rear admiral (Chester Ward), and so on and so forth. All ecosystems require critical mass. Chop down too much of the Brazilian rainforest and the jungle may go into a death spiral on its own. The same is true for the conservative media ecosystem in the 1960s. As an unintended consequence of technological innovation, conservative broadcasting could attain the critical mass necessary to persuade millions of listeners that conservatism was no longer a fringe ideology. It was self-authenticating in a way that was previously impossible.

This idea of a media ecosystem–although I’m not sure we used the term–came up briefly during our AHA panel Q&A. Nicole Hemmer noted that all media ecosystems have this self-authenticating epistemology. It is quite simple to construct a left-of-center media ecosystem that provides a similar self-authenticating function today. I might subscribe to the New York Times, check Slate and Vox on a daily basis, fill my social media feeds with like-minded liberals, and end up *knowing* that the news I receive is accurate because I’m hearing similar ideas across a range of sources. Sure, this can easily lead to group think–Someone like Trump could never win the presidency! No NBA team has ever come back from a 3-1 deficit in the finals!–but on some level we are forced to do so because we are inherently limited human beings who have neither the time nor skill to be experts in every subject. That doesn’t mean, of course, that all ecosystems are created equal, but it does mean that we all rely on ecosystems to provide our minds with an epistemological shortcut. Conservatives in the 1960s were no exception.